This fall, two challenges await visitors to the Fort Wayne Museum of Art in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The first is “Litmus Test: Works on Paper from the Psychedelic Era,” an exhibition of 80 or more pieces. The second is “All Access: Exploring Humanism in the Art of Chuck Sperry,” which promises 40 or so prints, original drawings, and tapestries by the San Francisco artist.

The first challenge will likely be easier for most viewers to pass, especially if they are fans of psychedelic rock art. Such viewers already embrace the iconography, attitude, and underlying idealism that characterized the better angels of the psychedelic era, to say nothing of the color riot that’s typical of the genre. But “Litmus Test” intrigues for its decision to bring together the work of actual rock-poster artists from the 1960s (San Francisco’s so-called “Big Five” of Wes Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Stanley Mouse, Rick Griffin, and Alton Kelley, plus Detroit’s Gary Grimshaw), a noted photographic chronicler of Detroit’s psychedelic scene (Leni Sinclair), and fine artists whose work has been influenced by the output of their graphic-art colleagues (Alex and Allyson Grey, Isaac Abrams). Completing “Litmus Test” is a bit of harmless nostalgia in the form of ordinary pieces of perforated paper pretending to be illicit sheets of blotter acid, prepared by the likes of Mark Mothersbaugh, H.R. Giger, S. Clay Wilson, and Chuck Sperry. It all sounds worth a visit, although “Litmus Test” is bound to be a cakewalk compared to the real thing to which the exhibition’s title alludes.

Chuck Sperry is the ostensible link between the two exhibitions, though more in spirit than by virtue of the coincidence of his contributions. In fact, Sperry’s “test” is actually much tougher than the one presented in “Litmus,” in no small part because of the uniformly beautiful appearance of his pieces. Sperry must know that some viewers will get no deeper than the surface of his work, misinterpreting his screenprints as contemporary updates of “pretty-girl art” from the 1940s and ’50s or the advertising graphics of Art Nouveau. Both of those associations are true enough as far as mere appearances go, but Sperry’s “ladies,” as they are known among rock-poster collectors, and “muses,” as they are called by those who gravitate to his fine-art prints, should really be seen as what the artist calls “utopian provocations,” intended as vehicles for social and spiritual transcendence rather than cheesecake to be ogled and vicariously consumed.

As if the sheer beauty of his work was not distracting enough, Sperry makes our leap of faith in his “provocations” even more complicated by literally wallpapering the skin of his silver-metallic beauties. The world, the artist appears to suggest, is preoccupied with external decoration—we have become experts at judging books by their covers. In the context of colorful utopian provocations in dark dystopian times, the trick is to figure out how to get past seductive surfaces in order to transform beauty into beautiful action.

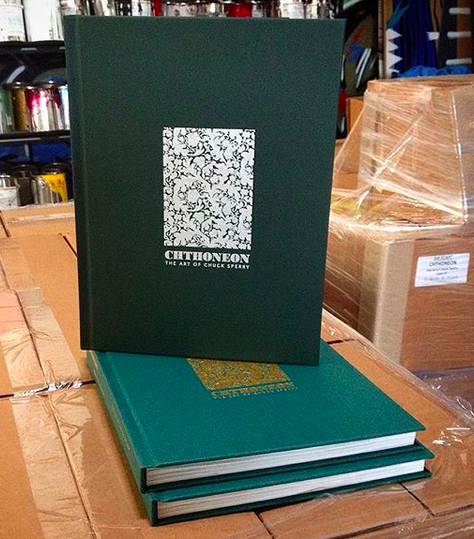

To help viewers get there, Sperry has released Chthoneon, the second of two self-published books about his work in as many years. As in Helikon, published in 2017, Sperry pairs reproductions of his art (via gorgeous photography by Shaun Roberts) with some of the literature that has inspired him. Helikon placed photographs of his muses, printed on wood panels, alongside their corresponding Orphic Hymns, some of which date to the 3rd century B.C. That book also gave us lyrics by Nick Cave, for whom Sperry has created numerous rock posters, as well as poems by Ovid, Homer, and Hesiod, along with the writing of a few contemporary authors.

At 136 pages, Chthoneon has a similar organization and format, although the literary focus is somewhat less reliant on the words of ancient Greeks. Sure, Aristophanes is represented, but other authors contributing poems and prose to Chthoneon include Margaret Atwood, whose dystopian Handmaid’s Tale has become a cautionary parable for our dystopian Trump-Pence-Kavanaugh era. Chthoneon also gives viewers who can’t make it to Fort Wayne their first look at three new tapestries Sperry had produced at Taller Mexicano de Gobelinos in Guadalajara, Mexico, whose artisans have made 10- and 11-foot-tall versions of “Thalia,” “Demeter,” and “Semele.” Enlarging his muses to heroic proportions puts them on a pedestal of sorts, which would seem to make them even less accessible to us mortals, but that’s just Sperry playing the sprite, goading us once again into finding the humanity in ourselves.

“Litmus Test: Works on Paper from the Psychedelic Era” and “All Access: Exploring Humanism in the Art of Chuck Sperry” open on September 14 with a party from 6 to 9 p.m. “Litmus Test” runs through November 11, 2018; “All Access” runs through December 9, 2018. For more information, visit the Fort Wayne Museum of Art.

This one article more than pays the cost of my membership