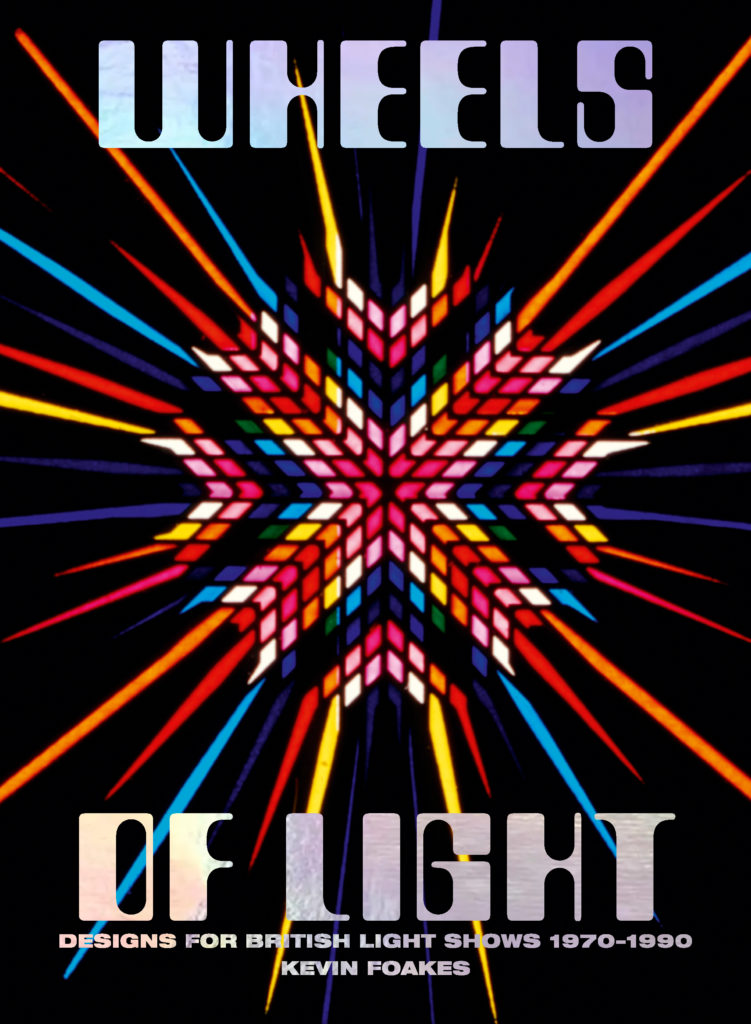

During the 1960s, San Francisco and London were well known for the graphic artists and rock musicians who created posters for and performed at venues such as the Avalon Ballroom and the UFO Club. Now, thanks to a handsome new book titled Wheels of Light, by Kevin Foakes, the London contribution to a third commonality between the two cities—the light show—is finally getting its due.

In San Francisco, light shows grew out of what artist Bill Ham has called the “experiments in painting with projected imagery” that were practiced by Elias Romero, who combined colored oils in glass bowls and set them on the fresnel lenses of overhead projectors to create light art at an old church on Capp Street. In 1964, playwright and director Lee Breuer invited Romero to illuminate the debut of his play, “The Run,” at the San Francisco Tape Music Center.

Around the same time, Foakes tells us in Wheels of Light, London artists Mark Boyle and Joan Hills were making light projections an integral part of their performance-art piece called “Suddenly Last Supper.” For that event, handmade films and actively combusting slides were beamed onto mannequins and performers alike.

In both cities, then, light shows began as a type of performed visual art or accompaniment to live theater. Before long, though, light artists realized that rock concerts were better suited to their illuminations, largely because the audiences at these psychedelic bacchanals were uniquely receptive to their work (i.e., they were high on drugs). It also helped that most of the bands playing the Avalon in San Francisco and the UFO Club in London “were happy to be hidden by the visuals projected over them,” as Foakes writes in Wheels of Light. Bands like Dantalian’s Chariot, Foakes continues, “even wore white and painted their equipment the same so as to blend in with the environment.”

Ham once told me a similar story about the time in 1966 when he lit a show at the Avalon headlined by the Grateful Dead. He and his assistant, Bob Fine, had gone to a fair amount of trouble to hang white plastic on the walls behind the band so they’d have something to project onto, only to have this pristine canvas for their light paintings obscured by stacks of the Dead’s equipment. After Ham explained to Owsley Stanley, who was in charge of the Dead’s sound at the time, what he was trying to do, Stanley had the band’s crew paint all the speakers white in time for the next evening’s show.

By 1970, Ham had left San Francisco for Europe, where he continued to do light shows until 1973 before returning home to paint with light there. During that same period, some London light-show artists were becoming light-show entrepreneurs.

to the glass as a mask, spray-painting it black, then removing the stickers with a blade.

The dots were then hand painted on the back of the glass using dyes.

Reading Wheels of Light, you get the distinct sense that this transition grew out of the ongoing necessity to MacGyver solutions to heretofore unknown problems. You know, like figuring out how to get colored oil that’s sealed within a sandwich of glass slides to move about so that the bubbly results could be projected onto a crowd of sweaty performers. “We used 2-inch-square slide cover glasses to make liquid slides which boiled in the projectors,” light-show artist and entrepreneur Neil Rice is quoted as saying in Wheels of Light, referring to his time with Ken Smith, with whom he put on light shows as Ono Yasumaro’s Illumination Factory. To reduce the boiling point of the colored oils in the glass slides so that their projectors did not have to run at furnace-like temperatures, Rice and Smith mixed their colors with ether, acetone, or methylated spirits. “To increase the heat on the slide,” Rice continues, “we modified the projectors so that we could raise and lower the heat filter in and out of the optical path. When this failed we resorted to using a gas blowtorch.”

Having mastered the subtler points of optical alchemy, Rice joined forces with Keith Canadine, who, with Jimmy Doody, ran a light-show-equipment company called Krishna Lights. Canadine, Foakes writes, “customized educational Rank Tutor 2 slide projectors, fitting them with slow-turning [½ rpm] motors that rotated discs with geometric patterns or liquid-filled wheels that would bubble and move once heated by the projector’s lamp.” For light show artists like Rice, this was some very cool stuff, but when Rice decided to sell his gear and replace it with the latest gizmos from Krishna, he “began to realize shortly afterwards that there was perhaps more money to be made selling light show equipment than using it.”

That epiphany led to Optikinetics, which was launched in the fall of 1970 by Rice, Canadine, and a fellow light-show-equipment tinkerer named Phil Brunker. Other companies playing in the same optical-effects sandbox at that time included Pluto Electronics, Orion Lighting, and Light Fantastic Limited, but Optikinetics was the big dog. Within a year and a half of its founding, the company was selling almost 200 pieces of light-show equipment a month. Some products were of their own design, resembling a security camera with a slot cut into it to hold bubbling glass slides and op-art cassettes, while others were basically slide projectors that had been hot-rodded to create brilliant optical effects.

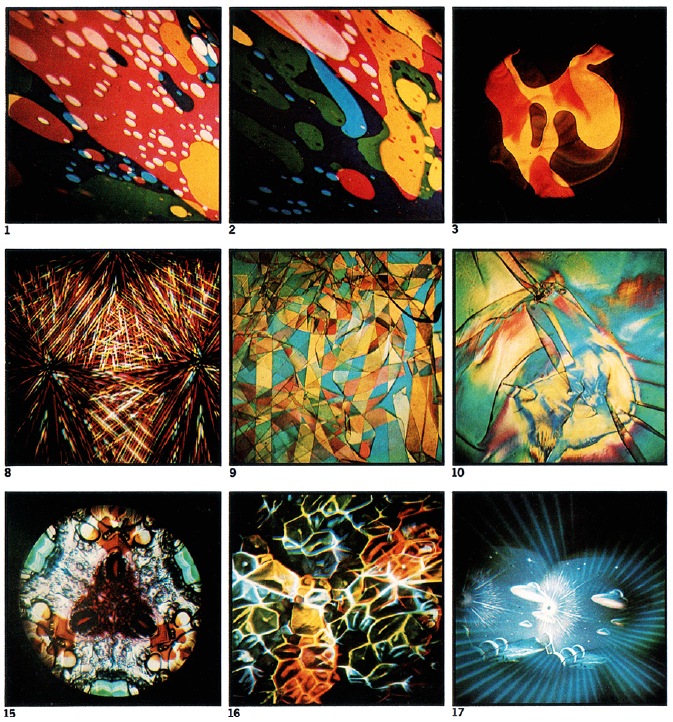

One evolving effect was the picture wheel, in which 360-degree circular paintings and illustrations by artists such as David A. Hardy, Steve Maher, Maggie Gould, Roy Wilkinson, and Jennie Caldwell were silkscreened onto six-inch discs that were then sandwiched between clear pieces of protective glass (later, plastic was employed). When combined with other effects—be they oozing colors or multi-colored moiré patterns—depictions of outer space, Roman orgies, and fantastical landscapes became wholly new and ever-changing optical effects, whose sum was always greater than their parts.

Most of the hardcover book’s 176 pages are devoted to high-quality photographs of these picture wheels and the three-inch cassettes responsible for those colorful, op-art moiré effects. While that’s probably what most readers want to see, and is solidly in keeping with the aim of the visually rich Four Corners Irregulars series, I’m a bit of a light-show nerd, so I look forward to a subsequent volume with more details about, for example, the large glass slides made by Neil Rice that “had syringe needles glued into them around the edges,” permitting a light artist to manually manipulate the colored liquids within them. Between this and the quote about the blowtorch, there appears to be an endearingly mad-scientist quality to Rice that sounds worth exploring.

It would also be illuminating to learn more about the role of women in the early days of light shows and at companies like Optikinetics. There, Foakes tells us, “The men worked on converting slide projectors to accommodate effects and the women hand painted glass effects plates over light boxes.” In fact, it’s impossible not to notice that many of the best (to my eye, anyway) picture discs in Wheels of Light were painted by women. I’ll bet those artists have a few stories to tell.

And finally, I sincerely hope this description of “Suddenly Last Supper” is true!

But I quibble. As a self-described visual history, Wheels of Light is a beautiful gift for those of us who thought we knew a thing or two about light shows, as well as those of us who simply appreciate the art form. You can order a copy directly from the publisher, Four Corners Books. And to learn more about light shows around the world, visit pooterland.com.

“Projected light” as an art form was happening in San Francisco well before 1964. The first “liquid light show” is known to have taken place in 1954 at SF State by Seymour Locks, and that isn’t even the beginning. There’s a contemporary desire to imagine that the UK and San Francisco happened upon this thing together, but this simply is not true.