Tucked away in a quiet corner of San Francisco’s Legion on Honor, the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts is far removed from the press of the museum’s usual crowds, befitting its role as a place where important scholarship and painstaking restoration routinely happens. Recently, about a dozen members of The Rock Poster Society got a peek of a small portion of the foundation’s collection and learned how Achenbach experts prepare old, battered, and often irreplaceable pieces of paper for exhibition.

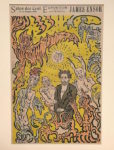

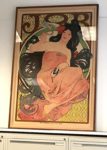

Our hosts were curator Colleen Terry and conservator Victoria Binder, both of whom made major contributions to last year’s Summer of Love exhibition at the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. After passing through the foundation’s study center, we entered a small room featuring a handful of Family Dog and Fillmore posters from 1966, as well as a larger selection of Art Nouveau lithographs from the years 1898 to 1913.

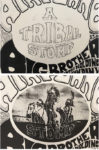

Of the new stuff, which is to say, the half-century-old rock posters, it was a treat to compare Wes Wilson’s original art for FD-01 and BG-29 with their subsequent offset lithos. In the case of FD-01, one can read instructions to the printer specifying that the words “A Tribal Stomp” be reversed so that they’ll appear as white letters on the photograph they’ll eventually overlay. Wilson’s original art for BG-29 and its two companion prints tell a different story—the first version was printed in black on white to meet a deadline; the “final” version, with its added colors of orange, purple, and green, was printed later.

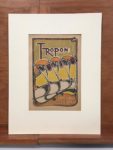

For rock-poster collectors, this is holy-grail material, but the antecedents of Wilson’s work was even more impressive. For me, the piece that stuck in my mind most was “Tropon,” an 1898 lithograph by Henry van de Velde, in which what appear to be stylized egg whites have fallen during separation from their yolks above. To my eye, this modest piece (roughly 12 by 8 inches) could be viewed as source material for some of the psychedelic reveries of Victor Moscoso, but even without that potential connection to the 1960s, the print stands on its own, a trippy little masterpiece of graphic design.

Our visit to Achenbach concluded with a demonstration by Anisha Gupta, the foundation’s Mellon Fellow in Paper Conservation, who explained how she used targeted heat to remove the backing from a rare World War I poster for an upcoming exhibition. Gupta and Binder also answered some of our questions about how rips are repaired and paper is cleaned without destroying a poster’s image. Suffice it to say, the techniques they described were not the sorts of things one should try at home, but it was comforting to know that one of the trickiest repairs for conservators also turned out to be one of the most common problems for collectors of old posters—removing Scotch tape.

(All prints are in the collection of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts)

Leave a Reply